Agent Native Architecture

Calibrating Autonomy and Predictability in Agent Systems

Abstract

This paper introduces Agent Native Architecture (ANA), a software design paradigm where an AI agent serves as the reasoning core of an application, with data structure emerging at runtime through the agent’s understanding rather than being predetermined at design time. ANA represents an evolution beyond AI-enhanced and AI-first approaches, inverting the traditional relationship between schema and understanding: structured data becomes an output of reasoning, not an input required from users or hardcoded by developers. The paper defines the core requirements for ANA, including a determinism model that places orchestration in the agent while tools provide predictable operations. The paper introduces the determinism spectrum as a key design dimension. A companion implementation explores these concepts through one point on this spectrum: a personal assistant that pushes toward high agent autonomy.

1. Introduction

The integration of large language models (LLMs) into software applications has followed a predictable pattern: take an existing application architecture, identify features that could benefit from language understanding, and add AI capabilities as an enhancement layer. This AI-enhanced approach treats the LLM as a sophisticated feature rather than a foundational component.

A more recent pattern, AI-first design, centers the application around AI capabilities from inception. However, even AI-first applications typically maintain traditional strict schema-driven architectures. The data model is defined at design time; the AI operates within those structural constraints. Some applications are beginning to blur these boundaries. Jottie, for example, extracts due dates and shifts classification from tag to entity as users type, without explicit field entry. I have no insight into Jottie’s backend implementation but suspect it exhibits some ANA properties.

This paper proposes a further evolution: Agent Native Architecture, where the LLM agent is not merely central but generative of structure itself. The schema emerges from the agent’s reasoning at runtime, rather than being predetermined by developers. Concurrent work by Shipper [4] explores similar territory from production experience—top-down learning from shipping products. This paper takes a complementary bottom-up approach. I highly recommend reading Dan’s post as well; different perspectives surface different insights, but encouragingly I noticed some convergence on key principles.

The paper proceeds as follows: I define ANA’s core requirements (Section 3), introduce a determinism model explaining where predictability lives in the system (Section 4), and map the design space architects must navigate (Section 5). I then examine capabilities and tradeoffs (Sections 6-7) before exploring a concrete implementation (Section 8). The contribution is the architectural framework; the application illustrates rather than defines it.

1.1 The Fundamental Inversion

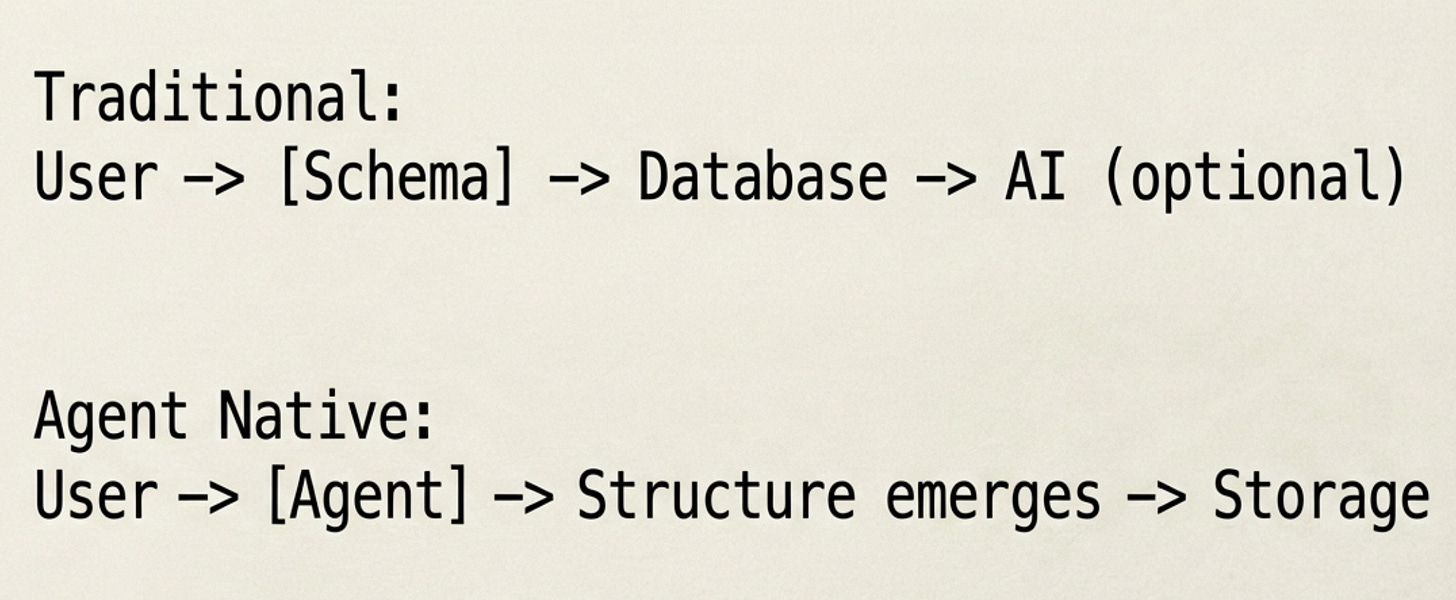

Traditional applications are schema-first: developers define data models, build features around them, then optionally add AI. The schema dictates what the application can understand and express.

Agent Native applications are semantic-first: the agent’s understanding of language and context is the core. Structured data becomes an output of reasoning, not an input required from users.

Consider a task management application. In traditional design, a Task model defines required fields: title, due_date, project_id, priority. Users must translate their intentions into this structure. In an agent-native design, the user says “remind me to call Mom before my flight tomorrow,” and the agent produces appropriate structure: a task linked to a calendar event, with temporal context. The user never needs to understand or manipulate the underlying schema.

This inversion has cascading implications for interface design, workflow flexibility, and emergent capabilities. Section 6 explores these in detail.

2. Defining “Agent”

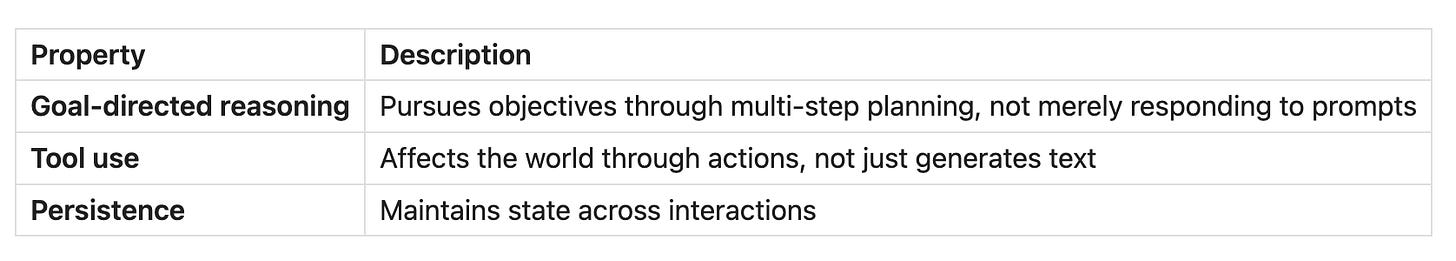

The term “agent” is overloaded in both AI and software engineering contexts. An agent can be defined as anything that perceives its environment and acts upon it, characterized by its operational domain and available tools [1]. For the purposes of Agent Native Architecture, I define an agent by three necessary properties:

These properties distinguish agents from adjacent concepts:

A stateless LLM call (inference) lacks all three properties

A chatbot with conversation history has persistence but typically lacks goal-direction and tool use

A workflow/pipeline with LLM steps may use tools but lacks autonomous reasoning. The orchestration is predetermined.

An agent combines goal-directed reasoning with the ability to affect state through tools, while maintaining memory across interactions. For short-running agents, persistence may be achieved through the context window alone; long-running agents require external memory mechanisms.

The term “Agent Native” therefore implies an architecture that supports goal-directed, tool-using, persistent behavior as a foundational capability, not an optional feature.

3. Core Requirements

For an architecture to qualify as Agent Native, three requirements must be satisfied:

3.1 LLM as Reasoning Core

The agent is the decision-making engine, not a feature layered onto existing logic. User intentions flow through the agent’s understanding before being translated into structured operations. This distinguishes ANA from AI-enhanced approaches where the LLM handles specific features (autocomplete, summarization, search) while traditional code handles core logic.

3.2 Runtime Schema Emergence

Structure is determined during execution, not fixed at design time. The agent decides what properties are relevant for a given item, what relationships exist between items, and how information should be organized. This does not mean the absence of schema. Rather, it means the agent participates in schema definition.

In practice, this manifests through flexible primitives. Rather than create_task(title, due_date, project_id), the agent operates with create_item(content, properties) where properties are open-ended. The generic term “item” is intentional; it carries no domain semantics. The agent decides whether this item is a task, note, reminder, or something else entirely.

3.3 Global Awareness

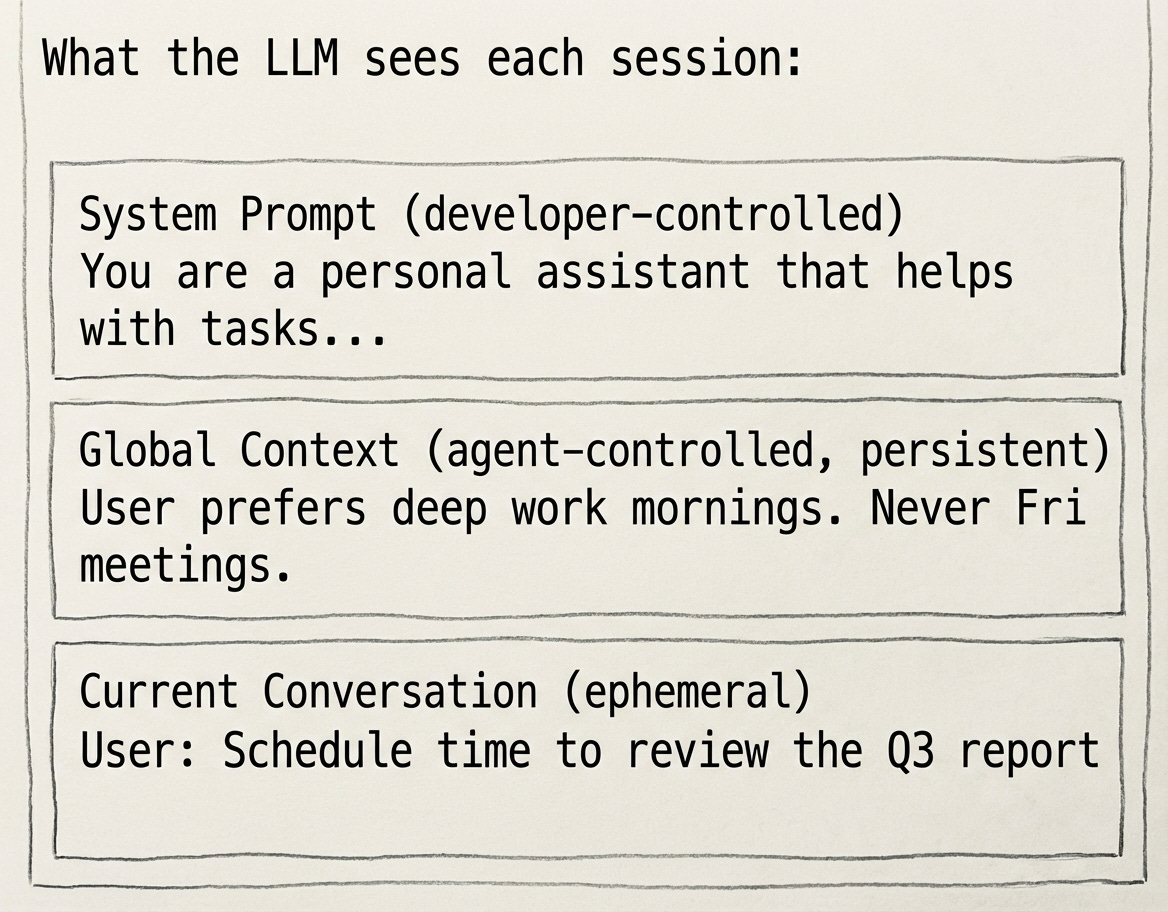

Agents require persistence across interactions to learn user patterns, maintain context, and improve over time. For agents operating across multiple sessions, this presents an architectural challenge: each new session starts fresh. The LLM receives the system prompt and the current conversation, but has no memory of prior interactions.

The system prompt is developer-controlled. It defines the agent’s persona: “You are a personal assistant that helps manage tasks and priorities.” But the system prompt cannot encode user-specific knowledge. It applies to all users equally.

ANA requires a mechanism for user-specific adaptation beyond the system prompt. The agent must accumulate knowledge about this particular user, including their preferences, patterns, constraints, and working context. This knowledge must shape reasoning in every session.

A naive approach stores everything in a retrievable memory system (RAG). The agent queries memory when relevant, surfacing past context. This works for episodic information (”what did I decide about the Q3 timeline?”) but fails for foundational preferences.

Consider: the user once mentioned “I prefer deep work in mornings.” With retrieval-based memory, this preference surfaces only when semantic search happens to find it relevant. The agent planning tomorrow’s schedule might not retrieve it. The agent suggesting a 9am meeting might not retrieve it. The preference exists in storage but doesn’t consistently shape reasoning.

The architectural insight: some knowledge must be constitutive of reasoning, always present and shaping every interaction. User preferences like “never schedule meetings on Fridays” need to inform planning consistently, not probabilistically. This knowledge belongs alongside the system prompt, present at the start of every session, not discovered through retrieval.

How this is implemented varies. The requirement is the capability: the agent must be globally aware of user-specific context that evolves over time, with foundational knowledge always present rather than retrieved. This insight emerged from my earlier work on implicit memory systems [3], where delegating memory decisions to the LLM revealed that contextual intelligence could replace programmed rules.

4. The Determinism Model

ANA introduces a specific model for where determinism lives in the system. This model inverts traditional software architecture.

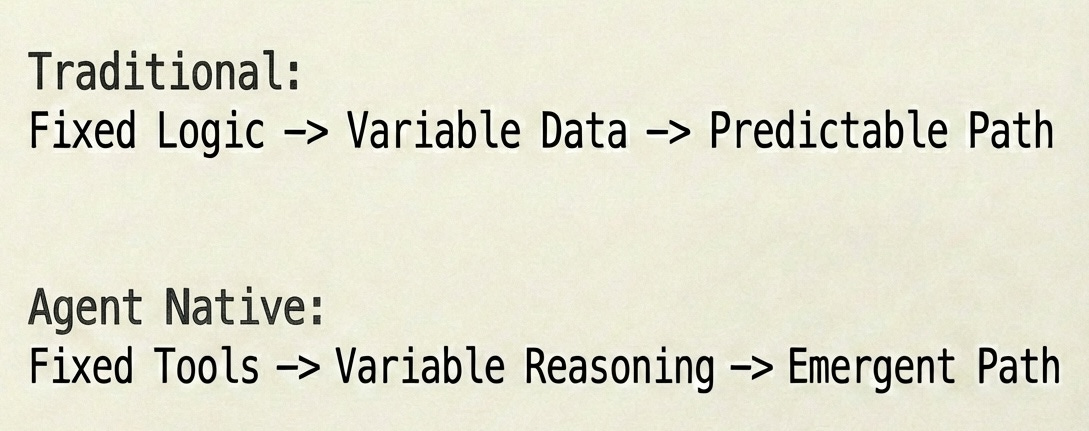

Traditional software: Code provides deterministic orchestration. Given state X and input Y, the execution path is predetermined. The developer specifies: “if user clicks submit, validate fields, then save to database, then show confirmation.” Data is the variable; logic is fixed.

Agent Native: Tools provide deterministic operations. Given a tool call with specific parameters, the result is predictable. But which tools get called, in what order, with what parameters is determined by the agent’s reasoning. Orchestration is the variable; operations are fixed.

Two distinct properties are at play:

Determinism is a property of the system: how predictable are outcomes given inputs?

Agent autonomy is a property of the agent: how much does the agent decide versus following predetermined paths?

Higher agent autonomy tends to reduce system determinism. This is not inherently good or bad. It creates risk, which may be acceptable or unacceptable depending on the domain. The architect’s role is to calibrate this risk.

Tools are the primary lever for adding determinism. A tool that enforces validation, requires confirmation, or constrains options adds predictability. The agent cannot circumvent what tools enforce. An ANA with no tools is just a stateless chatbot; tools are what make agents useful and what give architects control over system behavior.

System prompts also influence behavior, but with a softer guarantee. A prompt can instruct “always confirm before deleting,” and modern models follow such instructions somewhat reliably, but not absolutely—even frontier models achieve only around 80% accuracy on simple, unambiguous instructions [2]. Tools enforce; prompts guide. Section 5 explores how these surfaces combine.

This model explains why ANA is not “non-deterministic chaos” (see Section 7.1): every tool call is logged and traceable. System operators can observe what the agent did, audit decision patterns, and identify opportunities to improve. You gain adaptive capability by accepting that orchestration emerges from reasoning, but you retain visibility into that reasoning through tool-level observability.

5. The Determinism Spectrum

Section 4 established that tools provide hard determinism (guaranteed behavior) while prompts provide soft influence (reliable but not absolute). This section explores how these surfaces combine and how architects can position their systems along the determinism spectrum.

5.1 Influence Surfaces

Two primary surfaces shape agent behavior:

SurfaceNatureHigh ConstraintLow ConstraintToolsHard determinism: agent cannot circumventcreate_task(title, due_date, project)create_item(content, properties)Prompt GuidanceSoft influence: agent follows reliably but not absolutely”Tasks must have priorities 1-4” + rigid few-shot examples”Items can have any properties you find useful” + flexible examples

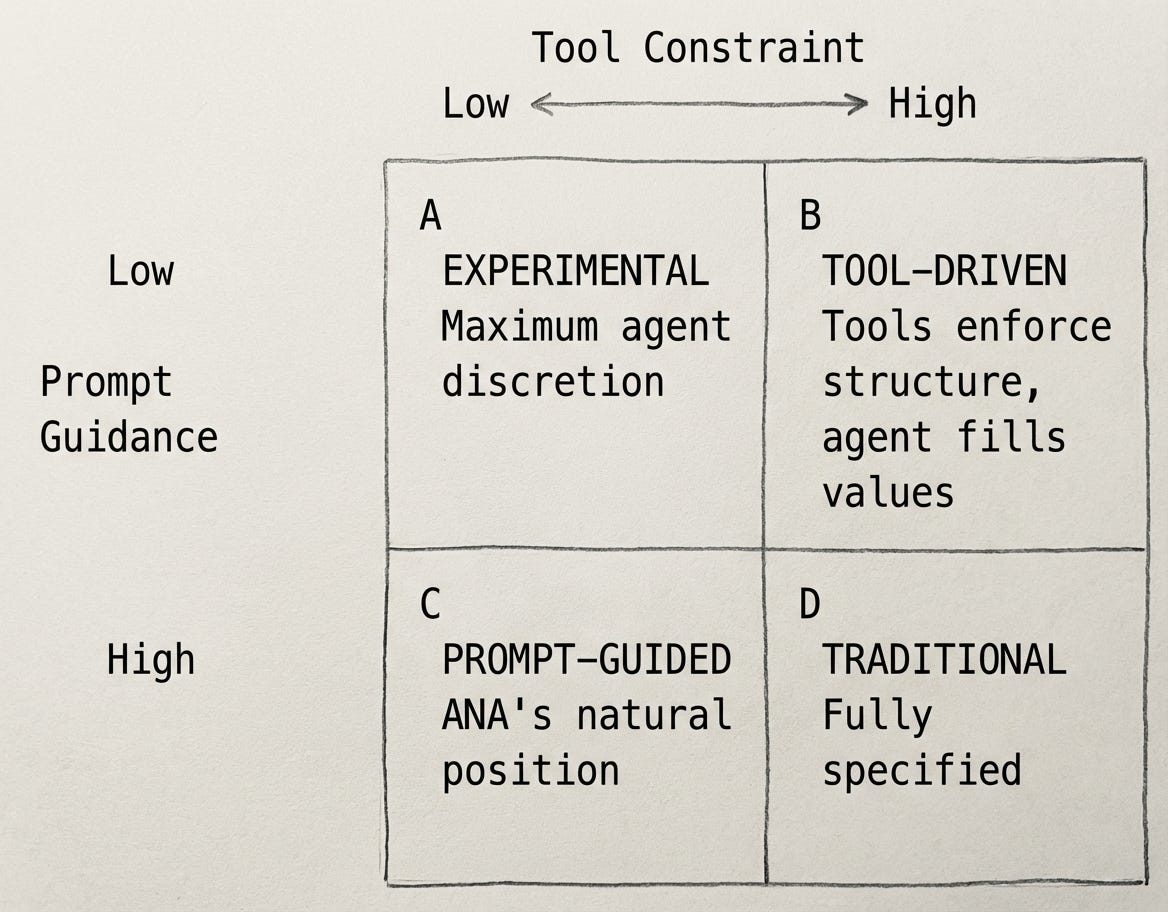

5.2 The Design Space

These surfaces create a two-dimensional design space:

Experimental (A): Maximum emergence. The agent decides almost everything. High adaptability but unpredictable. Useful for research; risky for production.

Tool-Driven (B): Domain concepts encoded in tools. The agent translates natural language into predefined structures. Predictable but inflexible.

Prompt-Guided (C): Generic tools with detailed guidance. The agent has operational flexibility but follows conventions. This is a natural position for ANA implementations.

Traditional (D): Fully specified behavior. The agent has little discretion. At this point, you may not need an agent at all.

5.3 Tool Constraint in Practice

Along the tool dimension, consider three levels:

High constraint: create_task(title, due_date, project). The schema is encoded in the tool signature. The agent translates natural language into predefined fields.

Medium constraint: create_item(content, properties). The operation is clear (create something), but the agent decides what properties matter. This is common in ANA implementations.

Low constraint: store(data). Minimal structure. The agent reasons about everything, including whether this is a create or update. High flexibility, but harder to observe and debug.

5.4 Finding Balance

Position on the spectrum is a design choice, not a quality gradient. Different applications warrant different positions based on their requirements for predictability versus adaptability.

A common effective pattern: medium-constraint tools with substantive prompt guidance (the Prompt-Guided quadrant above). This provides:

Operational clarity: You know what tool was called with what parameters

Domain flexibility: The agent decides what properties matter for each item

Behavioral guidance: The prompt teaches conventions without the rigidity of tool enforcement

This balance acknowledges a practical reality: even with generic tools, the agent will develop conventions. Prompt guidance shapes those conventions; tool structure makes operations observable.

6. Capabilities Enabled

The architectural choices above unlock capabilities that traditional approaches struggle to replicate. These are not features to be built; they emerge from the paradigm itself.

6.1 Contextual Flexibility

Users interact naturally without learning schemas. “Remind me to call Mom before my flight” becomes a task with temporal context. “Idea: what if we tried X?” becomes a note. The same primitive serves both. Users don’t choose between “create task” and “create note”; they express intent and the agent determines appropriate structure.

6.2 Cross-Domain Reasoning

Traditional applications require explicit integration work to connect domains. Flight data lives in one system, tasks in another, contacts in a third. An agent with access to multiple domains can reason across them naturally: flight times, task deadlines, contact timezone differences, and user preferences can all inform a single recommendation. This isn’t about eliminating structure; it’s about creating structure the agent can reason across rather than structure that isolates domains. Expose these domains through generic tools, and the agent can integrate them at runtime.

6.3 Emergent Features

Capabilities need not be predetermined. “Show me everything related to the Q3 launch” requires no special feature; the agent queries semantically. “What patterns do you see in my completed tasks?” requires no analytics dashboard; the agent reasons over available data. Features emerge from understanding combined with tools, not from predetermined code paths.

6.4 Immediate Personalization

Behavior adapts within conversations, not deployment cycles. A user says “I prefer deep work in the morning” once, and the agent remembers. No retraining required, no waiting for the next release. The Global Awareness requirement (Section 3.3) enables this: preferences become constitutive of reasoning, shaping all future interactions.

6.5 Proactive Behavior

Because the agent manages structure and maintains memory, it can notice patterns and initiate action: “You’ve rescheduled this task three times. Want to break it down or delegate it?”

This capability emerges directly from ANA’s core properties. The agent controls how information is structured, so it can organize data in ways that surface patterns. It maintains memory across sessions, so it can detect trends over time. And it reasons over both, identifying opportunities for intervention that a reactive system, waiting for explicit commands, would never surface.

Not all ANA applications require proactivity, but the architecture enables it. The agent has sufficient context (memory), capability (tools), and understanding (structure it created) to move beyond purely reactive behavior.

7. Boundaries and Tradeoffs

7.1 What ANA Is Not

Not “chatbot replaces UI.” Structured interfaces retain value for glanceable information, quick actions, and spatial navigation. The shift is in control: the agent becomes primary for complex or ambiguous tasks; structured UI handles rapid, well-defined interactions.

Schema is not abandoned. Tools impose the level of structure needed for a system. A create_item(content, properties) call requires content and accepts properties; this is a schema, just a flexible one. The agent produces structure; it does not avoid it. Items have properties; memories are retrievable by semantic relevance; operations have results. The difference is who defines that structure and when: the agent at runtime rather than developers at design time.

Not non-deterministic chaos. Tools provide deterministic operations (Section 4); the agent decides orchestration, but each operation is auditable and traceable. The agent’s reasoning is flexible, but the operations it produces are concrete and logged.

Not universally applicable. ANA suits domains characterized by ambiguity, personalization, and evolving requirements: personal assistants, knowledge work tools, creative applications. Systems requiring deterministic guarantees (financial ledgers, safety-critical systems) need architectural properties ANA does not provide.

7.2 The Core Tradeoff

ANA trades deterministic predictability for adaptive capability. In traditional architectures, behavior is fully specified: given input X, the system produces output Y. In ANA, behavior emerges from reasoning: given input X, the agent determines appropriate action based on context, memory, and understanding.

Observability as risk mitigation. Because every tool call is logged, system operators have an audit trail of agent decisions. This serves multiple purposes:

Debugging: When something goes wrong, trace back through the agent’s reasoning

Improvement signals: Is the agent repeatedly failing at certain tasks? Perhaps a new tool is needed. Are users asking for capabilities the agent can’t provide? That’s product insight.

Trust calibration: Observability data helps teams decide when to expand agent autonomy and where to add constraints

Observability doesn’t eliminate risk, but it makes risk visible and manageable.

Domain fit. This is an early-stage architectural experiment, and I resist prescribing where ANA belongs. That said, early patterns suggest fit varies by domain characteristics.

ANA aligns well with domains where:

User needs vary significantly and unpredictably

Concepts are fuzzy or evolving

Personalization provides substantial value

Contextual appropriateness matters more than exact reproducibility

ANA fits poorly where:

Regulatory requirements demand deterministic, auditable behavior

Errors have severe, irreversible consequences

Users need guaranteed response times

These are observations from early experimentation, not rules. The spectrum framework (Section 5) offers tools for calibrating ANA to specific domains rather than avoiding it entirely.

7.3 Trust and Transparency

Non-deterministic systems require different trust mechanisms than deterministic ones. Users cannot rely on “I clicked this button, so that happened.” Instead, trust builds through:

Explainability: The agent articulates its reasoning

Recoverability: Users can undo actions, correct misinterpretations, and refine preferences. The system doesn’t demand perfect communication upfront; it accommodates iteration.

Graduated autonomy: The agent earns expanded authority through demonstrated competence

Transparency: Users and system operators can inspect what the agent did and why

These mechanisms do not eliminate the trust challenge but provide a framework for navigating it.

The preceding sections define ANA as an architectural paradigm. The following sections explore these concepts through one concrete implementation: a personal assistant that sits toward the high-autonomy end of the ANA spectrum. This implementation illustrates the patterns; it does not define them.

8. Exploring ANA: A Personal Assistant

The companion repository implements ANA through a personal assistant application. This implementation sits toward the high-autonomy end of the spectrum: generic tools, flexible guidance, maximum room for the agent to reason.

Domain: Personal task and knowledge management, chosen for familiarity and discrete scope

Goal: Validate whether meaningful productivity features emerge from minimal primitives plus LLM reasoning

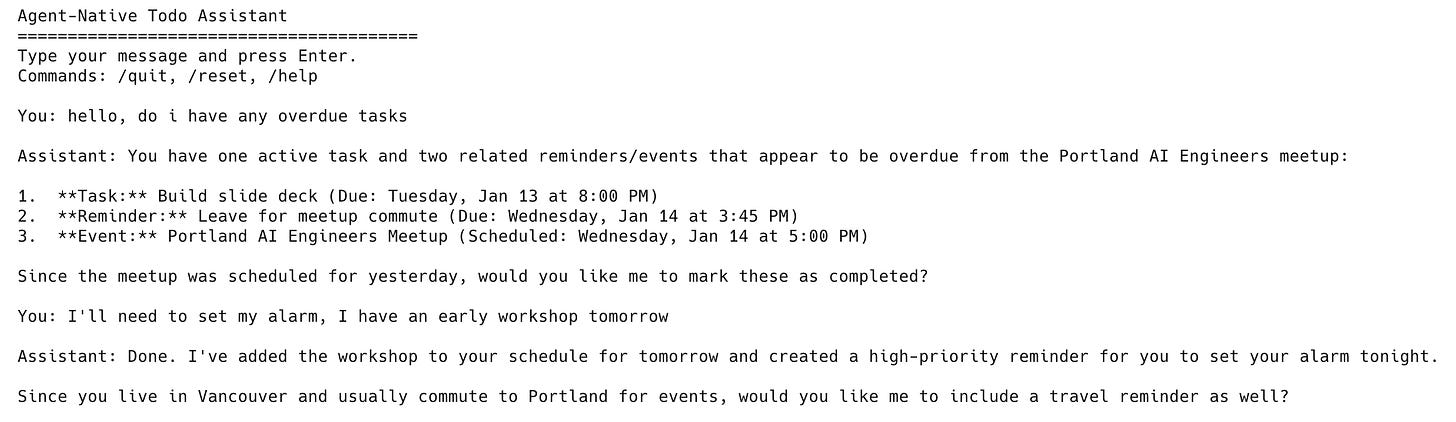

The interface is conversation-based—users express intent in natural language, and the agent handles all structure creation:

Above, the agent leverages global context knowledge to adapt to the user: “Since you live in Vancouver and usually commute to Portland for events, would you like me to include a travel reminder as well?“

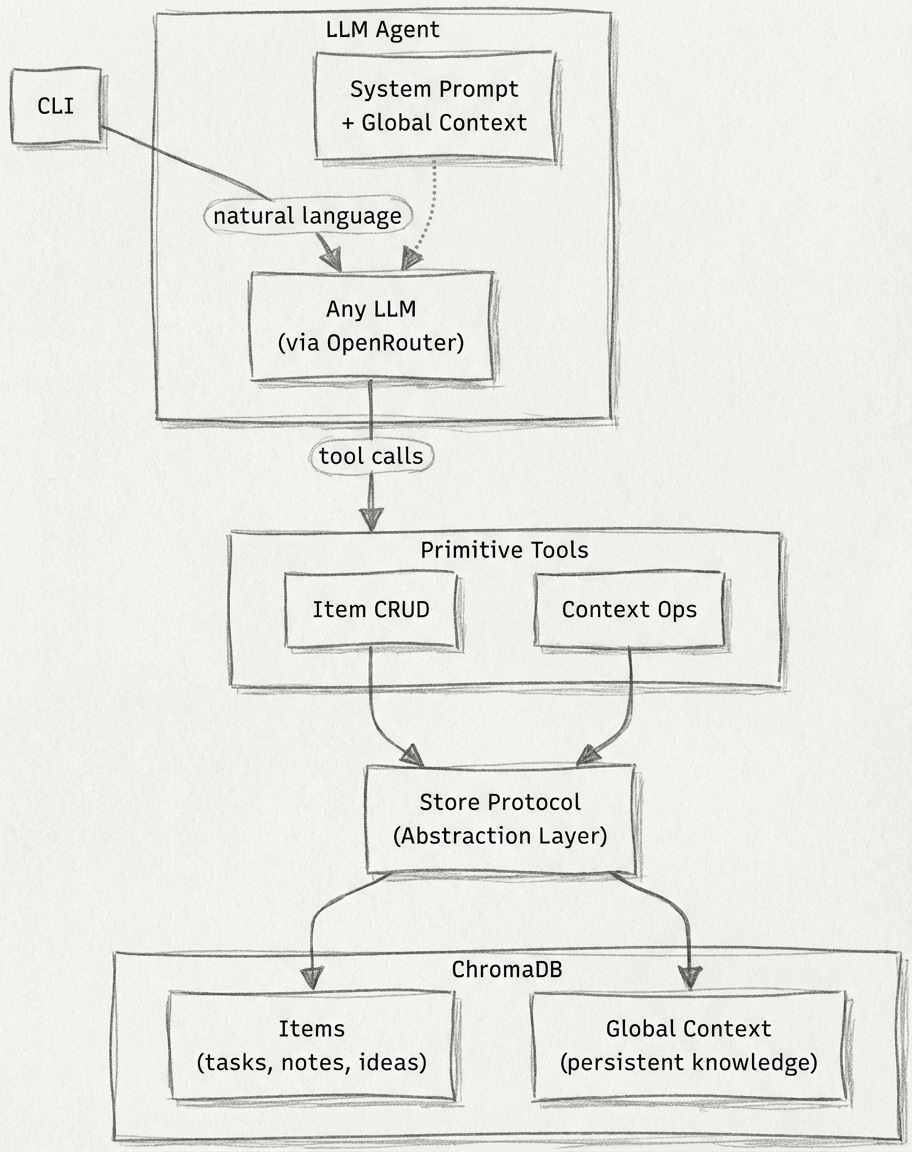

Under the hood, the architecture is intentionally minimal. Seven primitive tools connect the agent to storage, with a protocol abstraction allowing different persistence implementations:

8.1 Design Choices

Seven primitive tools with minimal constraint:

create_item,update_item,delete_item,query_itemsfor flexible itemsappend_context,replace_context,delete_contextfor Global Context management (these implement the constitutive knowledge mechanism from Section 3.3)

These tools provide operation-level determinism (for instance, you know a create operation occurred) without domain-level constraint (the agent decides what properties matter for each item).

System prompt providing domain guidance rather than rigid rules. The prompt teaches conventions (type: task, status: active) and suggests how to think about priorities, deadlines, and user context. But consistent with Section 4’s model, prompts steer rather than enforce. The agent exercises judgment within these conventions.

Single persistence layer using ChromaDB, a vector database that enables semantic search across all stored information. Every item is automatically searchable by meaning, not just keywords. This is an implementation choice, not an architectural requirement; the system abstracts storage behind a Store protocol allowing alternative implementations.

Conversation-based interface demonstrating the primary interaction pattern, with adaptive UI as a future extension (see Section 9).

One implementation detail worth noting: ChromaDB’s semantic search operates on document content, not metadata. Properties stored as metadata (e.g., due_date: "2026-01-13") are invisible to queries like “what’s due Tuesday?” The implementation addresses this by embedding properties into document content with dates converted to human-readable format, then stripping them on retrieval. This is a workaround for a specific persistence layer limitation, not an architectural pattern.

8.2 Global Context Implementation

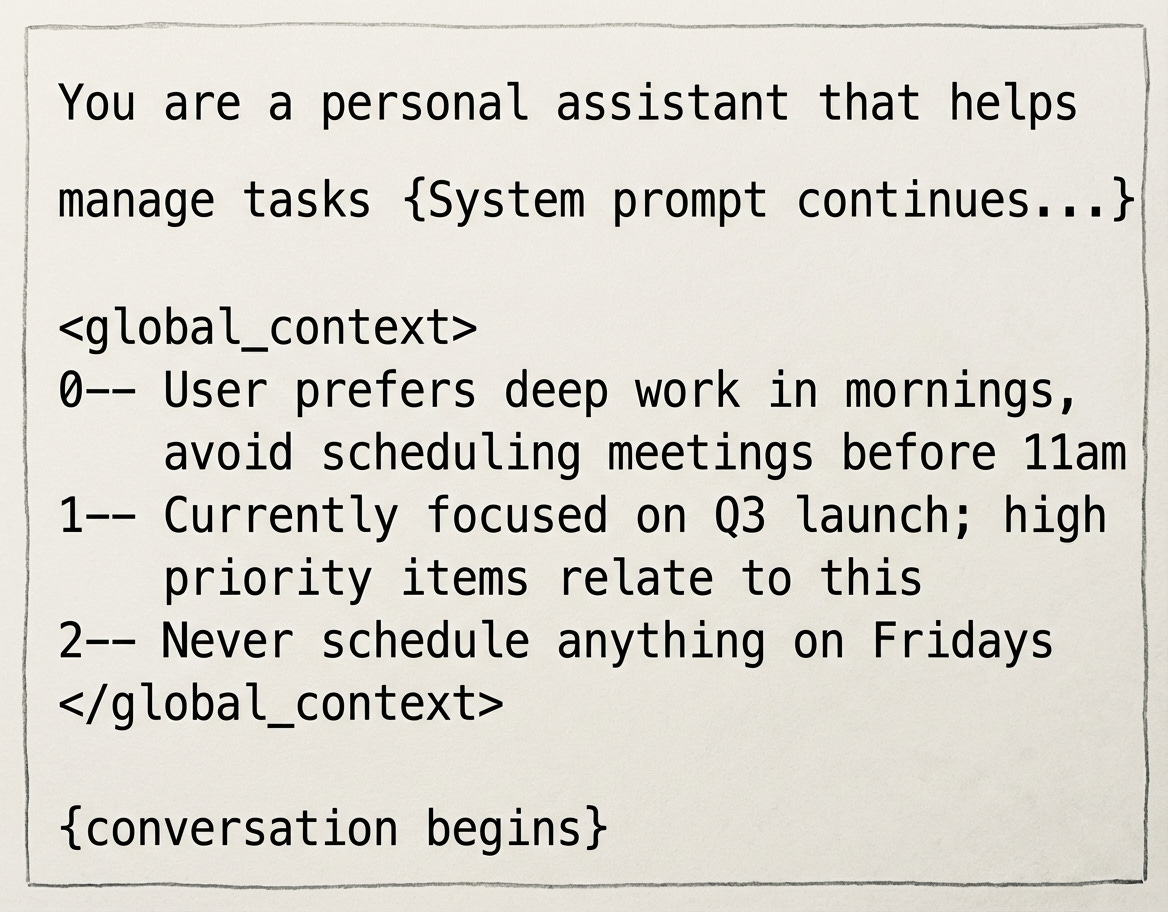

Section 3.3 establishes that ANA requires always-present foundational knowledge. This implementation addresses that requirement through Global Context: a separate ChromaDB collection injected into the system prompt for every interaction.

The implementation provides three tools for the agent to manage this knowledge: append_context, replace_context, and delete_context. The system prompt guides the agent on what belongs in Global Context (preferences, patterns, constraints) versus what should be stored as Items (tasks, notes, reminders).

In practice, the system prompt template includes a global context placeholder that gets populated before each LLM call. As mentioned the agent has tools to add, alter, remove entries by line number:

This structure makes accumulated knowledge constitutive of every interaction. For detailed design rati

onale, see the companion Global Context Design document.

9. Future Directions

9.1 Adaptive Interfaces

The ANA pattern extends naturally to user interfaces. The same principle, agent determines structure at runtime, applies to presentation.

Provide the agent with UI primitives (layout components, visualization types, interaction patterns) and interfaces can reshape based on user intent. “Show me tasks grouped by energy level, not project” becomes achievable without developer intervention. The agent reasons about what view best serves the current goal.

This represents the next experiment for the companion implementation: extending from conversation-based interaction to agent-driven interface adaptation.

9.2 Other Spectrum Positions

The companion implementation explores one position on the spectrum: high agent autonomy with minimal tool constraint. Other positions warrant exploration:

Lower autonomy: Domain-specific tools with more constraints, for applications requiring predictable behavior

Mixed positions: Higher tool constraint with flexible prompts, or rigid prompts with generic tools

Each position trades off differently between reliability and adaptability. The spectrum framework (Section 5) provides vocabulary for these design decisions; implementations across the spectrum would validate or refine the framework.

10. Conclusion

Agent Native Architecture represents a meaningful evolution in how LLM-powered applications can be designed. By positioning the agent as the reasoning core and allowing structure to emerge at runtime, ANA enables capabilities difficult or impossible to achieve in schema-first architectures: cross-domain reasoning, emergent features, immediate personalization, and proactive behavior.

A practical advantage deserves emphasis: ANA systems are significantly easier to tune toward desired behavior. Adjusting a system prompt or modifying tool definitions is far more accessible than refactoring tightly-coupled schemas. This makes iteration faster and lowers the barrier for non-engineers to shape system behavior.

The approach is not universally applicable. It trades deterministic predictability for adaptive capability, a tradeoff appropriate for domains characterized by ambiguity and personalization, inappropriate for domains requiring guaranteed behavior.

The key conceptual contributions are:

The fundamental inversion: Structure as output, not input

The determinism model: Tools enforce; prompts guide; agents orchestrate

The determinism spectrum: A design dimension for balancing reliability and adaptability

Global awareness: The requirement for user-specific adaptation with always-present foundational knowledge

I offer this framework not as a complete theory but as a working vocabulary for practitioners building LLM-centered applications. The paradigm is nascent; I expect the patterns to evolve as the community accumulates implementation experience.

References

[1] C. Huyen, “Agents,” January 2025. https://huyenchip.com/2025/01/07/agents.html

[2] N. Band et al., “Do LLMs Estimate Uncertainty Well in Instruction Following?,” ICLR, 2025. https://openreview.net/forum?id=PaFJmdKe0u (citing Sun et al., 2024 on GPT-4 achieving ~80% instruction-following accuracy)

[3] S. Keen, “Implicit Memory Systems for LLMs,” Deep Engineering, 2025.

[4] D. Shipper and Claude, “Agent-Native Architectures,” Every, 2025. https://every.to/guides/agent-native